The noise never stopped. Drills, engines, and men shouting into radios. The valley pulsed with it day and night. Walter Briggs had tried patience, phone calls, even the county office. None of it mattered. Every vibration rattled through his walls until even silence felt like something he’d imagined.

He told himself to endure it. To ignore the dust that settled on his porch, the lights that burned through his windows, the trucks that turned his fence into a target. He’d been through worse, he reminded himself. But he’d never had to watch his peace be stripped away like this.

That night, the lights from the construction site flooded his bedroom, and the steady hum of machinery kept him awake. He lay still, staring at the ceiling, feeling the weight of his years. He was too old for another fight, but too proud to give up what was his.

The land around Walter Briggs’s house was the kind of quiet most people didn’t notice anymore. His small home sat on the edge of the valley, a few miles past the last gas station, where the road narrowed and the sound of traffic disappeared. He’d lived there for twenty years, ever since he and his wife decided they’d had enough of city noise.

Each morning followed the same order: coffee, feeding the koi, checking the fence. He liked the routine. It kept things predictable. After the war, that mattered. He didn’t need surprises; he’d had his share.

The koi had been his wife’s idea, “Something peaceful,” she’d said when they first dug the pond together. She’d wanted color and life outside the kitchen window. After she passed, he kept them for her. The house creaked in familiar ways, the pond shimmered under the same light. Even the wind seemed to know its place.

That morning started the same way it always did until Walter noticed movement beyond his kitchen window. Across the field that bordered his property, three men were walking the land. They didn’t look like farmers or surveyors.

They wore pressed shirts, dark trousers, and carried clipboards. One of them pointed toward the ridge while another took notes. The third just stood still, talking into a phone. Walter watched for a while, his mug warming his palms.

That field used to belong to the Crawfords before they moved out west. He hadn’t met whoever bought it after. For all he knew, the men were insurance people or buyers checking the soil. Still, suits didn’t belong out here.

He stayed at the window until they headed toward their car, a shiny black sedan parked where the gravel road ended. When the doors closed and the engine started, the hum carried easily across the valley. Walter waited until the sound faded before turning away.

He set the empty mug on the counter and moved to his easel by the window. The morning light hit the sketch he’d left half-finished the day before: the pond, the fence line, and the old oak tree that had weathered every storm since he’d moved here.

He adjusted the chair, picked up a pencil, and tried to pick up where he left off. He’d drawn only a few lines when the doorbell rang. The sharp sound cut through the stillness of the house. Walter frowned, set the pencil down, and wiped his hands on a rag.

Hardly anyone ever came by unannounced. The mail carrier honked from the road if he had a package. The neighbors, what few there were, usually called first. He crossed the living room and opened the door.

A man stood outside, mid-forties, clean-shaven, wearing gray slacks and a rolled-up dress shirt. His car was parked at the edge of the drive. He smiled easily, like someone who’d practiced the expression in a mirror. “Mr. Briggs?” he asked. “Name’s Howard. I’m with Redline Development.” Walter held the screen door half-open. “What do you want?”

“Just a few minutes of your time. We’re developing the valley. Going to bring in some commercial spaces, retail, that sort of thing. We’re reaching out to property owners in the area. You’re on our list,” he said, smiling. “I’m not selling.” Howard nodded as if he expected the answer.

“I hear that a lot at first. But I think you’ll want to look at what we’re offering. We pay well above market value. It’s a good opportunity to get ahead of the changes that are coming.” Walter studied the man’s face. His smile didn’t quite reach his eyes. “Changes?”

“Construction,” Howard said. “Trucks, noise, all temporary, of course. But this whole stretch will be busy for a while. Best to move on before that starts.” Walter replied quickly, “I’m fine right here.” “Sure,” Howard said, still polite.

“But this is the last undeveloped section of the valley. Once work begins, you’ll be boxed in by the project. The view will be gone. It’s just the way progress works.” Walter didn’t answer. He could see the faint dust on the man’s polished shoes, the expensive watch glinting when he gestured.

Not a local. Not someone who understood quiet. Howard reached into a folder and held out an envelope. “Take a look when you get a chance. No rush.” “I won’t be needing it,” Walter said. Howard hesitated just a second too long before setting the envelope on the porch railing. “We’ll be in touch,” he said, and walked back to his car.

The sedan reversed slowly down the gravel, tires crunching until the sound faded into the open valley. Walter stood there for a while, the envelope untouched beside him. Then he picked it up, glanced at the Redline logo, and set it inside on the counter without opening it.

Outside, the land was quiet again, but it didn’t sound the same. The following weeks felt off in small ways at first. A few days after the salesman left, Walter noticed tire tracks near the bend in the road. Deep grooves cut through the soft shoulder, leading toward the valley floor.

The next morning, a flatbed truck passed carrying steel beams, its engine loud enough to rattle the windows. He watched it disappear beyond the ridge and told himself it was nothing, just roadwork or another farm changing hands.

But the traffic didn’t stop. Every day brought something new: dump trucks, graders, fuel tanks, even a portable office dropped off on the far end of the field. Men in reflective vests came and went, shouting instructions, pointing at blueprints, dragging survey tape that fluttered in the wind.

A week later, the same dark sedan returned. Howard stepped out, sunglasses glinting, his easy smile still plastered in place. “Just thought I’d check in,” he said, leaning against the car door. “There’s still time to make this easy on yourself, Mr. Briggs.” Walter shook his head. “You already have my answer.” Howard sighed, straightening his tie. “I figured you’d say that.”

His voice lowered. “But you should know, the work’s already approved. Once it starts, there’s no going back. Whatever happens from here… well, I tried to warn you.” He left without waiting for a reply. The car’s taillights disappeared into the dust, leaving Walter standing by the fence, his reflection faint in the truck’s window.

The words lingered long after the sound had faded, not a threat exactly, but close enough to feel like one. From his porch, Walter could see the change taking shape even before a single shovel hit the dirt. The grass was trampled, the horizon cluttered with equipment. His quiet corner of the world was turning into a staging ground.

At first, he tried to ignore it. He shut his windows to block the sound, moved his easel to the back room, and drew only at night. But the noise found its way in. Engines idled for hours. Backup alarms beeped in bursts. Metal clanged like gunfire when they unloaded supplies.

By the end of the first week, dust began to settle on everything, the porch railing, the koi pond, even the coffee cup he left outside each morning. The air smelled like diesel and wet cement. One afternoon, a cement mixer pulled too far forward on the narrow road, grinding over the corner of his lawn.

Walter walked out and waved the driver down. “Hey! You’re on private property,” he shouted over the engine. The man gave a lazy salute and reversed just enough to leave a deep rut in the grass. “Road’s tight,” he yelled back with a smirk. “Don’t take it personally.” Walter stood there until the truck disappeared, staring at the crushed patch of lawn.

That night, he filled it back in with soil from the garden and muttered to himself that it wouldn’t happen again. It did. The next evening, another driver used his driveway to turn around. The heavy tires tore through the edge of his flower bed.

Walter stormed outside, fists clenched, but the truck had already pulled away. All it left behind was the smell of exhaust and a splatter of mud on his fence. Soon, it was clear the damage wasn’t accidental. One night, just after sundown, a cement truck idled at the edge of the construction lot, headlights pointed directly at his front windows.

The beams cut through the living room like a spotlight. Walter waited, thinking the driver would move once he realized. But the lights stayed on. Five minutes. Then ten. The engine rumbled, steady and deliberate. He went outside and waved both arms. “Turn those off!” he shouted. A man stepped out of the cab, phone in hand, pretending to talk to someone.

“Didn’t see you there, old-timer,” he said with a grin. He climbed back in, revved the engine once, then finally backed the truck away, laughing as he drove off. Walter stood there, jaw tight, hands shaking. Inside, the walls still held the faint vibration from the engine. He turned off every light and sat in the dark until the ringing in his ears stopped.

The next morning his mailbox was torn off its post and lay face-down in the grass, the flag snapped off. Whoever had done it hadn’t bothered to hide the damage, just left it where anyone could see. Walter picked it up with two hands, set it back upright, and felt the slow, real annoyance settle in his chest.

When he called the county office to report the harassment, he was told to file a formal complaint online. “We need documented evidence,” the clerk said flatly. “Dates, times, photos. Without that, it’s your word against theirs.” He looked at his flip phone, at its smudged screen, and gave up halfway through trying to figure out how to email a picture.

Instead, he started keeping notes in a small spiral pad: April 11 – 7:40 PM, cement truck lights facing house, 10 min. April 12 – 3:10 PM, truck over lawn again. April 14 – mailbox on the ground The list grew quickly. Each day, something new. They parked closer. The generators ran longer. The trucks arrived earlier.

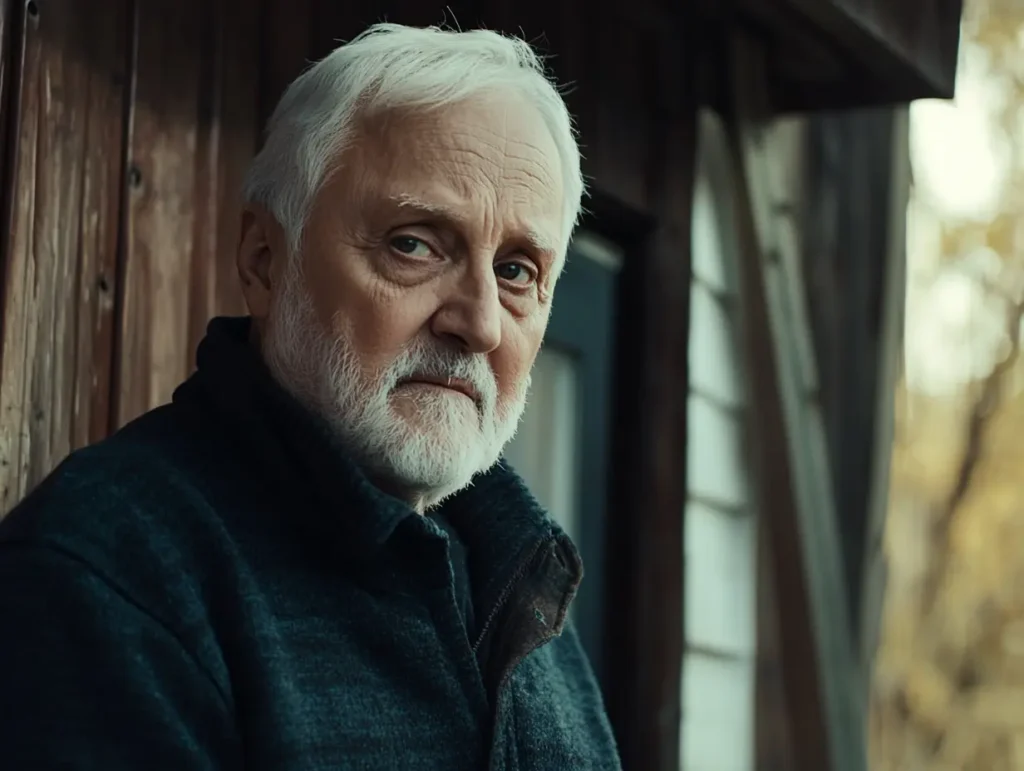

The valley’s once-quiet mornings turned into a low, constant mechanical hum. When Howard returned two weeks later, his tone had changed. The charm was still there, but thinner, stretched over something harder. He leaned against the gate like it belonged to him. “Mr. Briggs,” he said evenly, “we’re about to start groundwork. We’d really prefer to have this resolved before then.”

Walter kept his hands in his pockets. “I said I’m not selling.” Howard nodded slowly, studying him. “I get it. But you have to understand, this project isn’t going anywhere. And construction’s messy. Noise, dust, trucks running at all hours. It’s not going to be pleasant out here.” He smiled, but the warmth didn’t reach his eyes.

“Wouldn’t it be easier to move now, while you can still choose where to go?” “I built this place myself,” Walter said quietly. “I’ll decide when to leave.” For a moment, neither spoke. Then Howard’s smile flattened. “That’s your call,” he said. “But I’ll tell you this, in six months, you won’t recognize this valley.”

He straightened, tapped the gatepost with his knuckle, and added under his breath, “Don’t say I didn’t warn you.” He climbed back into his car and drove off without another word, leaving behind a low cloud of dust that hung in the air long after he was gone. That night, Walter didn’t bother drawing.

He sat on the porch until long after dark, staring at the faint glow of the work lights beyond the ridge. The quiet he’d once trusted was gone. In its place was a steady, distant hum that seemed to move under his skin. He wrote one last line in his notebook before bed: They’re not building yet. They’re just testing how much I can take.

By the third week, Walter had stopped pretending it would settle down. The trucks came earlier now, engines echoing off the hills before sunrise. When he stepped outside, the air already smelled of fuel. A haze of dust hung over the valley like a low ceiling. That morning, the noise was worse than usual, metal clanging, men shouting.

He followed the sound until he reached the edge of the construction site. A cluster of vehicles idled near a line of stacked concrete pipes. At the center of it all stood the foreman, a stocky man in a hard hat and safety vest, barking orders to the crew. Walter called out from the fence. “Hey! You the one in charge here?” The foreman turned, eyes narrowing under his helmet.

“Who’s asking?” “Walter Briggs,” he said. “That’s my property you’ve been running over. You’ve been keeping me up every night with your trucks. I can’t live like this. I’m seventy-one years old. I can’t manage this kind of noise.” The foreman crossed the dirt lot, boots grinding into the gravel.

Up close, he looked more like a man used to paperwork than machinery; clean nails, a neat clipboard. “Mr. Briggs, right? I heard about you.” He smiled, almost kindly. “I get it. Change is hard. But there’s nothing personal going on here. We’re just doing our job.”

“It feels personal when your people drive through my yard,” Walter said. “When they park with their lights in my windows.” The foreman’s expression softened for a moment, as if he truly understood. “Look, I can ask the drivers to be more careful. But the bigger picture… that’s above my pay grade. Redline makes the calls.”

Walter’s voice cracked with fatigue. “Then tell Redline this is a nightmare. You can’t keep working like this next to people’s homes.” The man exhaled, hands on his hips. “Between you and me, Mr. Briggs, you could make this a lot easier on yourself. Redline’s offering good money. Take the deal, buy a smaller place somewhere quiet. That’d solve everything.”

“I’ve got nowhere else to go,” Walter said. His throat tightened. “This is my home.” For a moment, the foreman’s sympathy vanished. His tone hardened. “Then I’m afraid you’ll have to live with the inconvenience. We’re breaking ground next week. And just a heads-up. You can expect some water interruptions. We’ve got to reroute a line before pouring the foundations.”

“Water interruptions?” He nodded. “Yeah. County pipes. Might go dry for a few days. Nothing we can do.” Walter stared at him, feeling something collapse inside. “You can’t just shut off water to people’s homes.” The foreman shrugged. “You’re not the only one affected. It’s temporary.”

He checked his clipboard, already done with the conversation. “Why don’t you head back, sir. It’s noisy out here.” Walter opened his mouth to argue, but the man had turned away, shouting at another worker. The engines roared again.

Walter walked home slower than usual, his shoes coated in pale dust from the road. The low hum of machinery followed him up the hill, steady and relentless, like a headache that never eased. He’d tried everything; talking to the crew, to the foreman, even the county office. Every time, he got the same polite shrug. Nothing we can do, sir.

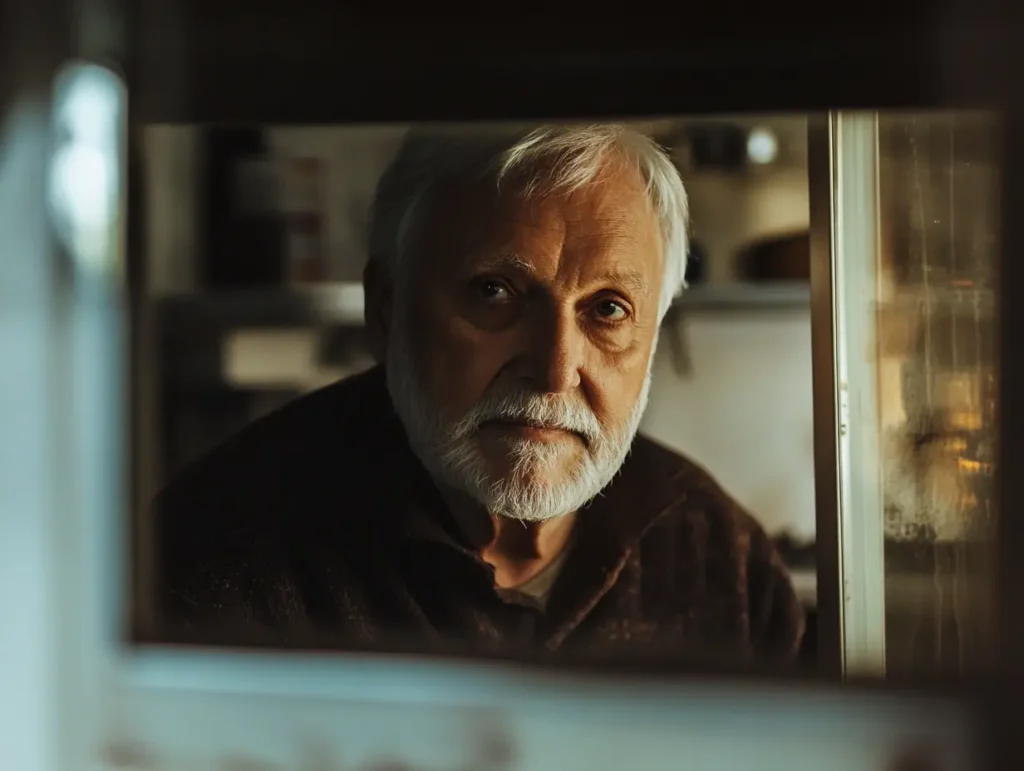

He felt smaller with every encounter, like the land itself was being chipped away from under him. The walls of his house seemed to lean in closer each day, holding in the noise, the vibration, the smell of diesel that clung to the air. He poured himself a cup of coffee he didn’t want and stared out the kitchen window, where the evening light hit the pond just right.

Maybe the fish would calm him, like they always did. But when he stepped outside, his stomach dropped. The pond’s surface shimmered wrong. It felt broken, uneven. Two koi flopped helplessly near the edge, their bright scales catching the porch light as they struggled for air. The filter gurgled dry, sucking nothing but air. “No, no, no,” Walter muttered, rushing forward.

He waded into the shallow water, scooping one fish into his hands. Its body twitched weakly, gills pulsing open and closed. He ran to the faucet by the garden. Nothing, just a dry hiss. He tried the one by the shed, then the kitchen sink. All dead. The bastards had shut the water off again.

He leaned against the counter, chest tight, the sound of the struggling fish carrying through the open door. Those koi had been his wife’s idea. Her last project before she got sick. “Something peaceful,” she’d said. “A little color outside the window.” Walter had kept them for her. He couldn’t lose them too.

He grabbed the old well pump from the shed, set it up beside the pond, and prayed the motor still worked. When it sputtered to life, sending out a thin stream of water, he almost cried from relief. He filled a large plastic tub, the kind he used for soil, and began transferring the koi one by one. They thrashed at first, then quieted as he poured more water over them.

He knelt there in the dirt beside the tub, his clothes soaked, hands trembling. The fish were safe for now, but his patience wasn’t. Something inside him cracked that night, quiet but final. Walter didn’t sleep that night. The house felt hollow, the hum of the distant generators leaking through every wall.

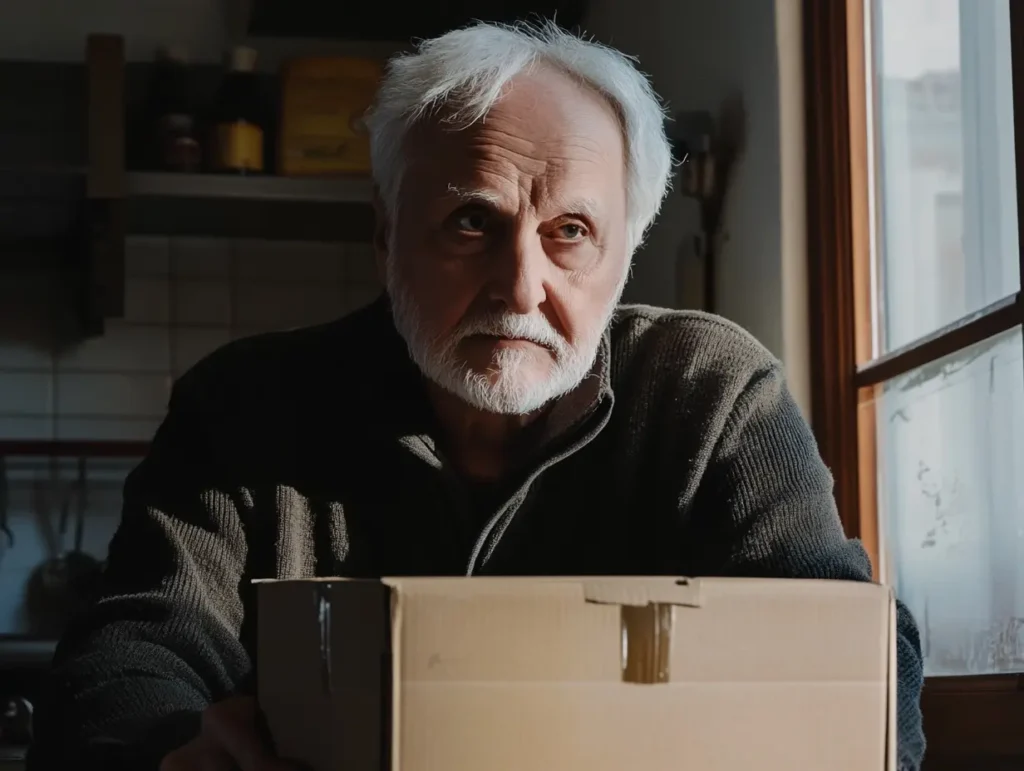

He sat at the kitchen table, staring at the old wooden box in front of him. Inside were a handful of spent shell casings; brass, scuffed, harmless. Leftovers from years ago when he still hunted on weekends. He hadn’t touched them in years, but now they gleamed like opportunity.

The plan wasn’t much of one. Just a distraction. Something to make the company slow down. The casings had no powder, no risk just enough to look suspicious if a metal detector swept by. He figured they’d have to stop and bring in the county to make sure the site was safe. Maybe it would buy him time.

Maybe it would remind them that not everything underground belonged to them. He waited until the lights over the valley dimmed and the workers’ voices vanished. The night was still, the sky a thin wash of gray-blue, and the only sound was the crunch of gravel under his boots.

He carried a small shovel and a pocketful of brass. When he reached the construction site, he stood for a long moment at the edge of the churned dirt where they were planning to pour foundations the next morning.

Walter stepped over the caution tape and moved quickly. He dug shallow and uneven holes, just deep enough that the brass would glint under the first layer of soil but not vanish completely. A few here, a few there. He worked methodically, pressing the casings into the dirt, tamping it down with the flat of his boot. The ground was cold and smelled of oil and wet concrete.

Every time a night bird cried out, his pulse jumped. When he was done, he stood at the edge of the pit, breathing hard. His gloves were damp, his shirt clinging to his back. He looked at the disturbed soil, at the faint shine of brass under the moonlight, and whispered to himself, “That’s enough.”

Back home, he scrubbed the dirt from his hands and tossed the gloves into the burn barrel behind the shed. Then he sat on the porch until dawn, the empty coffee cup cooling between his palms. He knew it was stupid and risky too but the thought of slowing them down, even for a day, gave him a flicker of relief he hadn’t felt in months.

By midmorning, as he watched from his porch, the first excavator rolled into the pit and stopped. A worker shouted for the foreman, waving something small and metallic. The commotion spread quickly. Within an hour, the trucks were parked, the workers gathered, and a white county van pulled up with Municipal Safety stenciled on the side.

Walter sat still, pretending to read the paper, his heart hammering. He wanted to feel triumphant, but all he felt was a heavy, anxious quiet. By late morning, the site looked more like a crime scene than a workplace. County inspectors in bright vests walked the perimeter, while workers stood in uneasy clusters.

From his window, Walter watched one of them kneel and lift something small and metallic from the dirt. It was one of his casings. Another found a second, then a third. The foreman barked into his phone, pacing near the pit, throwing furious glances toward the hill where Walter’s house sat. Walter felt his pulse in his throat. He hadn’t meant for this to spiral.

It was supposed to be a nuisance, not a scandal. He told himself again that he had emptied every casing. There was no danger, no explosive material. But each shout from below made his stomach twist tighter. When a county van rolled in with hazard markings, his palms went damp. Maybe he’d gone too far. Maybe they’d start asking questions.

Then the sound came. A hollow metallic thud from somewhere deep beneath the ground. Everyone on site froze. A breath later, a violent crack followed by a deep, rolling boom shook the valley. The ground quivered under Walter’s boots as his windows rattled. A plume of gray dust shot up from the pit.

Shouts erupted. Workers scrambled away from the trench, some diving behind vehicles, others sprinting for the access road. Walter stumbled onto the porch, gripping the railing. His first thought was disbelief. He’d made sure they were harmless, just brass, nothing else. His second thought was panic. What if I missed one?

Sirens wailed in the distance, growing louder. The first fire trucks appeared minutes later, followed by county emergency vans. Yellow tape went up fast, the area sealed off. Walter stayed frozen where he stood, his mind racing through every detail; the gloves, the shovel, the holes. He hadn’t left a trace. But still, his gut twisted like he had.

As the bomb squad arrived and began setting up floodlights, Walter backed into his house. Through the curtains, he watched them sweep the pit with detectors, their movements slow and deliberate. Radios crackled. Someone shouted the words unexploded ordnance. Walter’s knees nearly gave. He sank into a chair, staring at his hands, whispering, “It can’t be me. It can’t.”

By the next morning, the valley had transformed. Trucks lined the dirt road, and a small army of officials moved methodically through the dig site. The bomb squad worked in silence, lifting soil in thin layers, scanning every inch. They uncovered more metal fragments and then, something heavier. A corroded ammunition box.

The foreman’s jaw tightened as they lifted it out. Minutes later, another was found. And another. Before long, the pit was dotted with stacked wooden crates, their stenciled markings barely visible through the rust. Someone from the county museum arrived, murmuring about old military storage. The words Civil War era passed between the inspectors.

Walter watched from his porch, stunned. The very thing that had haunted his past had been lying beneath their boots all along. He hadn’t caused the explosion. The land itself had. Methane pockets, decaying munitions, time. His little act of rebellion had merely uncovered what history had hidden.

Later that day, an officer from the municipality climbed the hill to speak with him. “Mr. Briggs,” he said, holding his helmet under his arm, “we’ve finished the sweep. Your property’s clear. Nothing dangerous under your home or pond. Looks like the storage site ended just past your fence line.”

Walter nodded slowly, exhaling for what felt like the first time in days. “So it’s safe then?” he asked, keeping his voice steady. The officer gave a small smile. “Safe as it gets. Whatever’s under there’s been buried longer than either of us has been around.” Walter nodded again, his shoulders finally easing.

By week’s end, Redline Development pulled out completely. The land was designated a protected recovery area and no future construction permitted. The floodlights were dismantled, the noise gone. What remained was silence, wide and familiar.

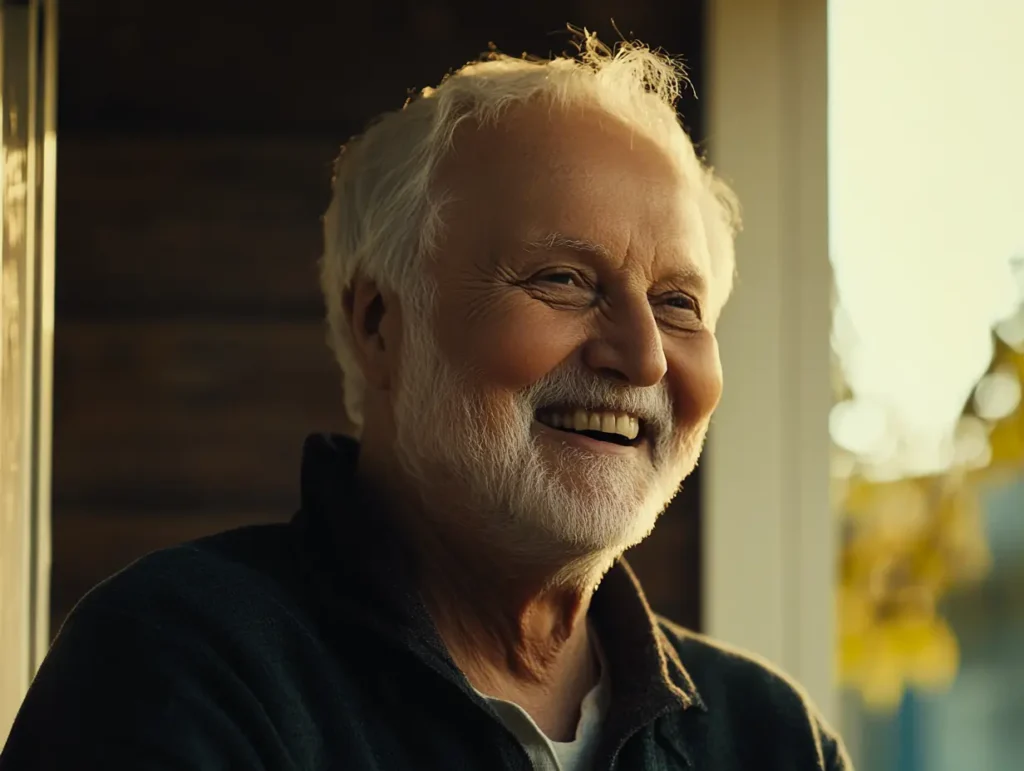

That evening, Walter fed the koi in the clean pond. The water shimmered gently under the fading sun. The air smelled of wet grass and the faint mineral scent of well water. He sat back on his porch, hands steady for the first time in months, and watched the fish glide in slow, peaceful circles.

A laugh escaped him. One that was soft, tired, and disbelieving. The war he’d spent a lifetime trying to forget had ended up saving the only peace he had left. For once, the quiet didn’t feel fragile. It felt like it belonged to him again.