Maxine burned in Mike’s arms, her skin too hot, her body frighteningly still. She didn’t cry. That was the worst part. Babies cried when something was wrong. Maxine only whimpered once, a thin sound that faded as quickly as it came, her head heavy against his chest while Carrie fumbled for the thermometer with shaking hands.

The number blinked back at them, impossibly high. Carrie swore under her breath. Mike was already moving—keys, shoes, the diaper bag knocked over in his haste. His thoughts chased each other in tight circles: what she’d eaten, how long she’d slept, whether he’d missed something obvious. She had been fine yesterday. Laughing. Reaching for him.

Outside, the night was eerily calm as they rushed toward the car. Maxine’s breathing was shallow, uneven. Mike pressed his forehead to hers for half a second, whispering her name like it might anchor her. Somewhere between the apartment and the hospital, a thought took hold that made his chest tighten with dread: this hadn’t come out of nowhere. Something had been happening to their daughter—and they were only just beginning to see it.

Mike Armstrong used to think happiness would feel louder. He had imagined it as something obvious—celebratory, unmistakable. Fireworks. Big moments. Proof that life had finally tilted in his favor. But when Maxine was born, happiness arrived differently. It settled. It stayed. It breathed. She was small, pink, and impossibly warm against his chest.

Mike remembered the weight of her that first night, how afraid he’d been to shift even an inch, terrified he might do something wrong just by existing too close to her. Carrie had watched him from the hospital bed, exhausted and smiling through tears, and whispered, “You can breathe. She’s not made of glass.” But she felt like it. Maxine was everything they had waited for.

Everything they had almost stopped believing would happen. The years before her had been quiet and heavy with disappointment. Doctor visits that blurred together. Test results delivered in careful tones. Friends announcing pregnancies with apologies in their eyes. Carrie handled it with grace most days. Mike less so. He counted months. Counted money.

When Carrie finally told him—hands shaking, voice barely steady—that she was pregnant, he sat down on the kitchen floor and cried. Not loudly. Just enough to scare himself. Maxine arrived after a long, complicated pregnancy and an even longer labor. She arrived perfect anyway.

They didn’t have much. Not in the way people usually meant it. Mike worked maintenance for a commercial building downtown. Carrie managed a small team at a logistics firm—steady work, decent pay, no safety net. Their apartment in Pittsburgh was clean but cramped, with thin walls and a view of the parking lot instead of the river. They made it work.

They always had. The early months of Maxine’s life passed in fragments—night feedings, half-slept days, milestones noticed more by feel than by calendar. The first laugh. The first word. The way she reached for Mike’s face and gripped his beard like it was something solid she could trust. He’d never felt more useful in his life.

By the time Maxine was two, she was a bright, chatty toddler with opinions about everything and a laugh that filled rooms. She followed Carrie from room to room, asking questions that came too fast to answer. She called Mike “Da,” with complete confidence, like there was no question he would always come when she said it.

Then reality pressed in again. Carrie’s maternity leave had ended long before Maxine learned to talk, and the years since had been a careful juggling act. Mike’s hours couldn’t bend enough to cover everything. Daycare costs were staggering—more than their rent some months, more than Mike brought home. Every option felt like a gamble.

“I hate the idea of strangers,” Carrie admitted one night, rocking Maxine as she drifted to sleep. “She’s still so little.” Mike knew what she meant. He pictured drop-offs, unfamiliar hands, rooms full of crying children.

The thought made his stomach knot. That was when Carrie suggested her mother. Eleanor Whitman had never been cruel. That wasn’t the problem. She was precise. Opinionated. Certain.

She had raised Carrie alone after her husband died young and wore that fact like armor. She believed experience outranked advice, and age made rules unnecessary. Mike respected her. Mostly. “She knows babies,” Carrie said. “She raised me. And Maxine already loves her.” That part was true. Maxine lit up when Eleanor entered a room.

Maxine reached for Eleanor with an enthusiasm she didn’t give easily. Eleanor took her without hesitation, holding her with the kind of practiced confidence that came from having raised a child once before. She settled Maxine against her hip, already murmuring to her, already in charge.

Mike felt his chest tighten. It wasn’t distrust, not exactly. He loved Eleanor. He respected her. But since Maxine had been born, the circle of people he trusted with her well-being had narrowed until it was almost painfully small. Himself. Carrie. That was it. Everyone else—even family—felt like a risk he hadn’t agreed to calculate.

“It’s temporary,” Carrie said quickly, as if she sensed the hesitation before he voiced it. “Just until we figure something else out.” Temporary made it easier to nod. Easier to tell himself that this wasn’t giving something up—just borrowing help.

Eleanor began watching Maxine during the weekdays at her own home. Every morning, Mike and Carrie packed the same small bag—snacks, spare clothes, a stuffed rabbit Maxine refused to nap without—and drove across town before work.

Eleanor always met them at the door, already dressed, already prepared, her house quiet and orderly in a way that made it feel more like a schedule than a home.She believed in routines. In calm. In not “overstimulating” children with noise or clutter.

She cooked her own meals, favored natural remedies, and spoke with the assurance of someone who trusted experience more than instruction manuals. When she offered advice, it sounded sensible—especially when delivered with the confidence of a woman who had raised a child before.

“She’s old-school,” Carrie said when Mike raised an eyebrow at something Eleanor suggested. “She means well.” And she did. At least, that’s how it looked. For the first few weeks, everything seemed fine. Maxine smiled when her parents came to get her. Eleanor reported peaceful naps, good behavior.

She talked about the baby the way people talk about something they believe belongs partly to them. Then small things shifted.Maxine slept more. Too much, maybe. She wasn’t fussy—just quiet. When Mike picked her up after work, she felt heavier in his arms, not because she’d gained weight, but because she didn’t push back. Didn’t wriggle. Didn’t reach.

“She’s just tired,” Eleanor said lightly. “Babies grow in phases.”Carrie nodded, relieved to accept an explanation. Mike watched. Not accusing. Just noticing. He told himself not to read into it. They had wanted this help. Needed it. Eleanor was family.

The first thing Mike really noticed was the silence. Maxine had always made noise before. Small sounds, but constant ones—little hums, half-formed words, the occasional squeal when something caught her attention. Now, when he arrived at Eleanor’s house in the evenings, the rooms felt muted in a way that had nothing to do with Eleanor’s insistence on calm.

Maxine was usually in her grandmother’s arms, eyes half-lidded, her head resting heavily against Eleanor’s shoulder. She didn’t twist to look at the door anymore. Didn’t lift her arms. “She’s been so peaceful today,” Eleanor would say, smoothing Maxine’s hair.

“You’re lucky. Some parents would kill for a child this easy.” Mike smiled when expected. Kissed his daughter’s forehead. Told himself not to linger on how cool her skin felt. Carrie noticed things too, but she framed them differently. She always had.

“I know I keep asking if it’s a growth spurt,” she said one night, scrubbing a pan that was already clean, “but… this doesn’t feel normal anymore.” Mike nodded. “It’s not random,” he said. “It’s patterned.” Weekends felt different.

On Saturdays, when Maxine stayed home with them, she fussed. She cried. She demanded attention in ways that were exhausting but familiar. By Sunday afternoon, she smiled again—hesitant at first, then wider.

By Monday evening, Maxine was quiet once more.Mike didn’t write it down. He just counted. Days with Eleanor. Days without. One afternoon, they stayed longer than usual at Eleanor’s house, lingering in the kitchen while Maxine played on the back patio. The late light slanted through the windows, warm and deceptive.

Eleanor was mid-sentence when something moved outside. Fast. Carrie startled, turning toward the glass. “Did you see that?” Mike was already there. The garden lay still for a second—too still. Then something darted past the fence line, low and quick. Eleanor jumped this time, a sharp sound leaving her throat.“What was that?” Carrie asked.

They stepped closer to the window. A blur slipped between the plants and vanished through the far corner of the yard. A moment later, a tail flicked into view. “A cat,” Eleanor said, exhaling. “Just a cat.” Relief came quickly. Too quickly. Mike’s eyes stayed on the fence. One of the lower boards had shifted, loose enough for something small to squeeze through.

Near the flowerbed Maxine liked to dig in, dark clumps dotted the soil. “That’s new,” Mike said. Carrie followed his gaze. “Could she be allergic?” she asked. “That would explain the fevers.” It made sense. Too much sense. The kind of explanation that slides neatly into place and asks no further questions. Mike crouched, inspecting the gap. “I’ll fix it,” he said immediately.

He did it that weekend. Hammering boards back into place. Reinforcing the corner. Scrubbing the stones near the garden bed until his hands ached. Each nail driven felt like action. Control. Hope. For a moment, it worked. And then nothing changed. Maxine’s fevers returned by Wednesday. Then came the tea.

It slipped out casually, the way harmless things often do. Carrie was bathing Maxine when their daughter touched the water and murmured something soft and garbled. “Flower,” Maxine said. Carrie laughed, then paused. “Flower?” “Flower tea.” Carrie looked up slowly. “Mom,” she called. “What kind of tea have you been giving her?”

Eleanor appeared in the doorway before the question had fully landed. “It’s our routine,” she said. “Maxine and I pick flowers from the garden together. She loves it. We make tea.” Mike’s stomach tightened. “Flowers?” he asked. “Are you sure they’re safe for a child to ingest?” Eleanor’s expression hardened. “It’s all natural. I’ve been drinking the same teas for years.

And I only grow the best ones in my garden. Trust me—nothing harmful comes out of my soil.” The way she said it—final, unquestioning—made Mike nod when he shouldn’t have. They asked her to stop anyway. Eleanor agreed too quickly. “Fine,” she said, smiling thinly. “If it makes you feel better.”

For a few days, it did. Maxine slept better. She laughed once—a soft, startled sound that made Carrie freeze mid-step and smile like she’d just been handed proof. Then the fever came back. Higher this time. By Friday, Maxine wouldn’t eat.

“I keep asking myself what I’m missing,” Mike said quietly that night, standing beside the crib. “What’s wrong with my child?” Carrie didn’t answer. She didn’t have one. The next morning, Mike arrived early at Eleanor’s house without calling ahead. The place smelled faintly floral. Not unpleasant. Just unfamiliar.

Eleanor stood at the counter with her back to him, pouring something from a small pot into a mug. Maxine sat in her booster seat, feet kicking weakly, eyes fixed on the cup. Mike stopped just inside the doorway. “What’s that?” he asked. Eleanor startled, nearly spilling the liquid. She turned too quickly, the mug clutched tight in her hand. “Nothing,” she said at once.

“Just warm water.” Maxine let out a small sound—half whine, half plea—and reached for the cup. “It’s tea,” Mike said flatly. Eleanor’s shoulders stiffened. “She asked for it.” We asked you not to,” he replied. Eleanor’s mouth pressed into a thin line. “I wasn’t going to deny her something that soothes her,” she said.

“You don’t refuse a child when they’re asking for comfort.” Mike stepped closer. He could see bits of plant matter clinging to the rim of the mug. Tiny petals. Pale stems. “You don’t know what she’s ingesting,” he said. “I know my garden,” Eleanor snapped. “Better than you ever will.” That night, after they brought Maxine home, her fever climbed higher than it ever had before.

By morning, she wouldn’t wake. At first, Mike told himself she was just sleeping deeply. Babies did that. But when her eyelids didn’t flutter at his touch and her body stayed limp against his chest, fear hit him so fast it stole his breath.

Carrie didn’t wait for him to speak. She was already dialing, her voice cracking as she described the fever, the lethargy, the way their daughter hadn’t responded at all. Bring her in now, the nurse said. The emergency room was a blur of motion and clipped voices. Maxine was taken from Mike’s arms almost immediately. A nurse called out her temperature.

Another placed a tiny oxygen monitor on her foot. Carrie stood frozen until Mike pulled her back into motion, both of them answering questions they barely processed. Then Maxine vomited. It was sudden and violent, her small body jerking as the nurse turned her on her side. The smell was sharp, sour, unmistakably wrong.

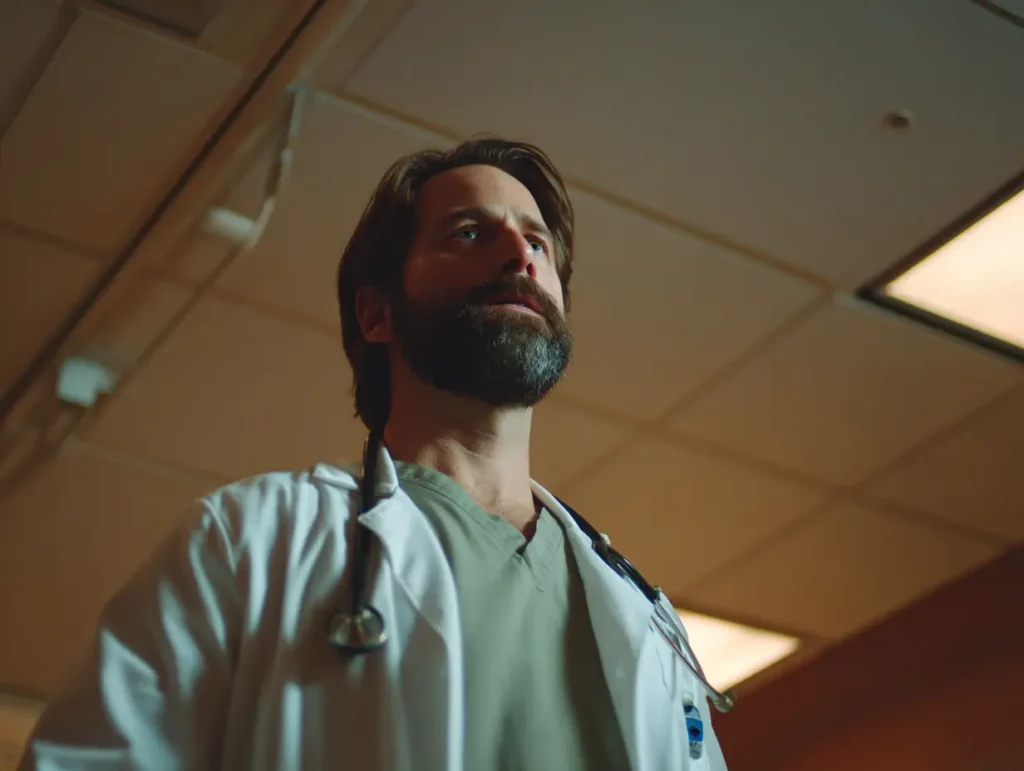

Mike felt his stomach drop as a doctor stepped in, expression tightening. “That’s important,” he said quietly. They moved quickly after that. Fluids. Bloodwork. Monitoring. When the doctor returned, he didn’t sugarcoat it. “We’re concerned about food poisoning,” he said. “Something she ingested isn’t agreeing with her system.

Her stomach is irritated, and it’s been happening for a while.” The word poisoning lodged in Mike’s chest like a splinter. Carrie shook her head. “That doesn’t make sense. She eats what we give her. We’re careful.” The doctor nodded. “I believe you. But babies don’t get this sick without repeated exposure. We need to know everything she’s been consuming.

Not just meals. Liquids. Supplements. Anything outside the usual.” Mike felt heat rise up his spine. “The tea,” he said suddenly. Carrie turned toward him. “What?” “My mother-in-law,” Mike said, the words coming faster now. “She watches Maxine during the week. She’s been giving her herbal tea. Said it was natural. From her garden.”

The doctor’s brow furrowed immediately. “Tea?” he repeated. “What kind of tea?” “She said chamomile. Flowers. Other things,” Mike said, anger sharpening his voice. “We told her to stop.” The doctor exchanged a look with the nurse beside him. The pediatrician listened without interrupting.

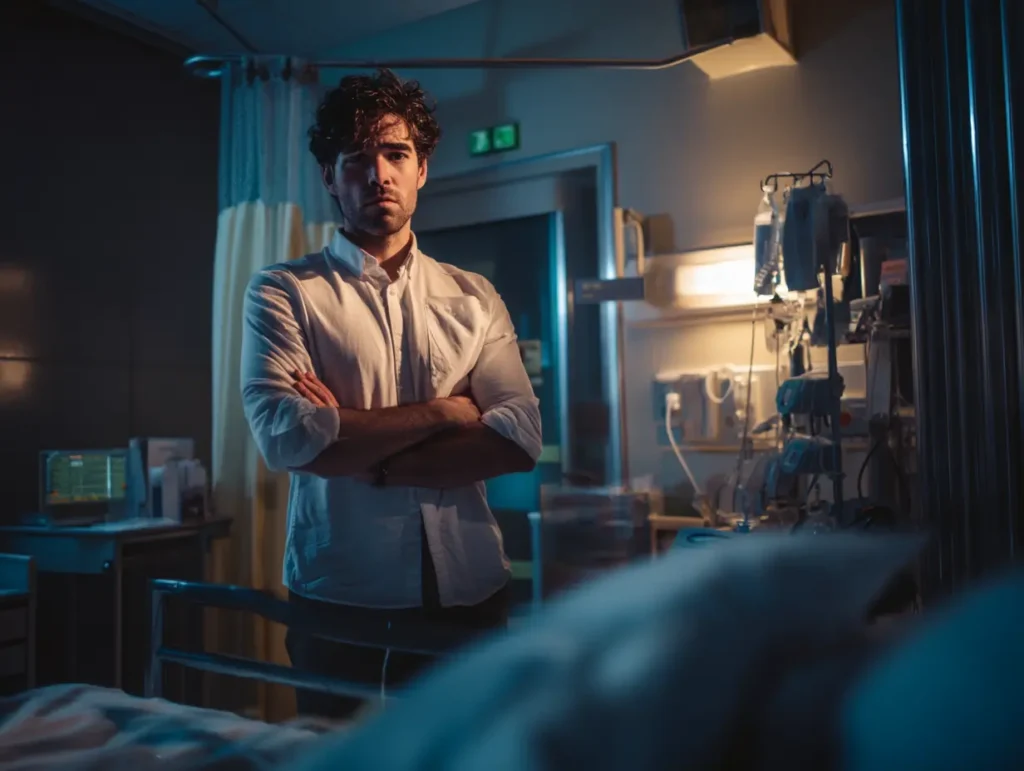

Mike stood rigid beside the hospital bed, arms crossed, while Carrie spoke in short, careful bursts—about the fevers, the weight loss, the fatigue that came and went without warning. About Eleanor. About the tea. When Carrie finished, the doctor nodded once. He didn’t look surprised.

“I want to be very clear,” he said. “It’s highly unlikely that properly prepared herbal tea caused this.” Mike felt a strange flicker of relief—and immediately after, dread. “So it’s not the flowers?” Carrie asked.

“Not in the way you’re thinking,” the doctor replied. “Most common herbs would cause stomach upset at worst. Nausea. Maybe mild dehydration. They don’t explain malnutrition, recurring fever, or this level of lethargy.”

He gestured gently toward Maxine, small and still beneath the blanket. “This looks like repeated exposure to something her body can’t process,” he continued. “Not a one-time ingestion. And not something she should have been consuming at all.”

Mike swallowed. “You’re saying… poisoning?” The doctor hesitated. Just long enough. “I’m saying we need to identify everything she’s been in contact with,” he said carefully. “Food. Drink. Environment. We’ll test the tea ingredients to be thorough—but I don’t expect them to be the source.”

Carrie’s voice cracked. “Then what is?” “That’s what we’re going to find out,” the doctor said. “But whatever it is, it’s been happening over time.” Mike looked at his daughter again. Her chest rose and fell, shallow but steady. He tried to think backward—days, weeks, patterns.

Nothing made sense. “And the grandmother?” Mike asked quietly. The doctor met his eyes. “I’m not assigning blame,” he said. “But I will need samples from the garden. Soil. Plants. Anything your daughter may have touched.”

Mike nodded. As he stepped into the hallway to make the call, one thought settled heavily in his chest: If it wasn’t the tea— then it was something closer. Eleanor answered on the third ring. “Is she awake?” she asked immediately, voice tight with concern. “I was just about to head over—”

“You need to come to the hospital,” Mike said. He didn’t raise his voice. That scared him more than if he had. “Now. And you need to bring samples from your garden. Everything you’ve been using.” There was a pause. Not confusion. Calculation.

“My garden?” Eleanor said. “Mike, I already told you—” “The doctor wants them,” he cut in. “Flowers. Leaves. Soil. Anything Maxine might have touched.” Another pause. Shorter this time. “I’ll be there,” she said. “Of course I will.”

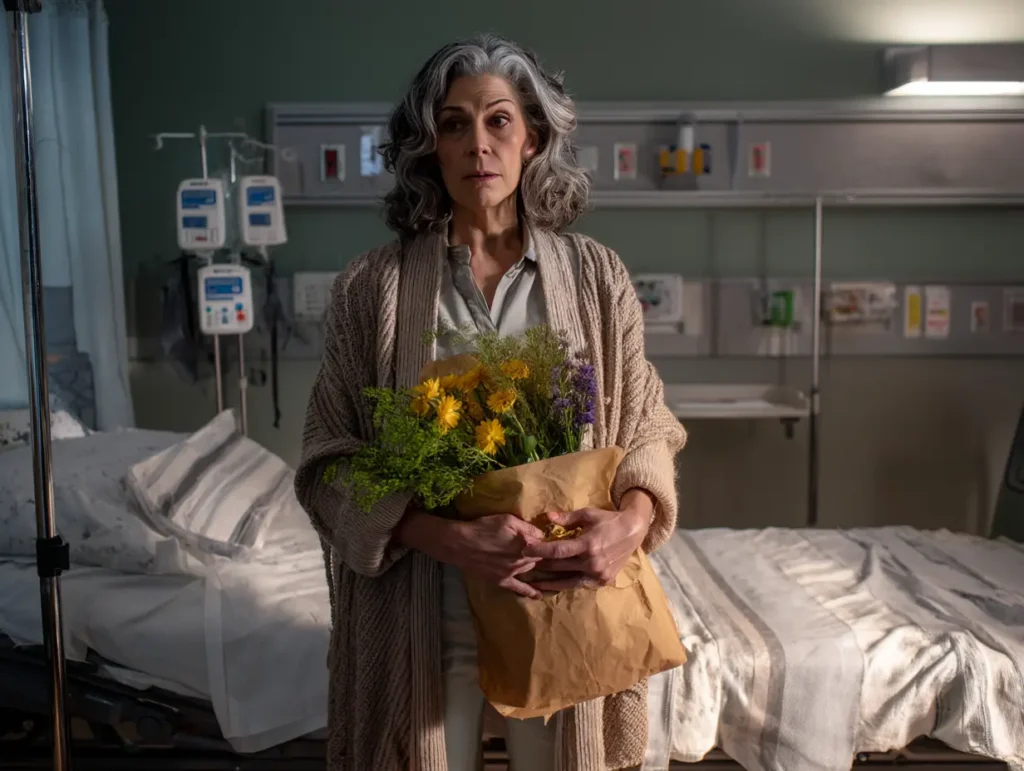

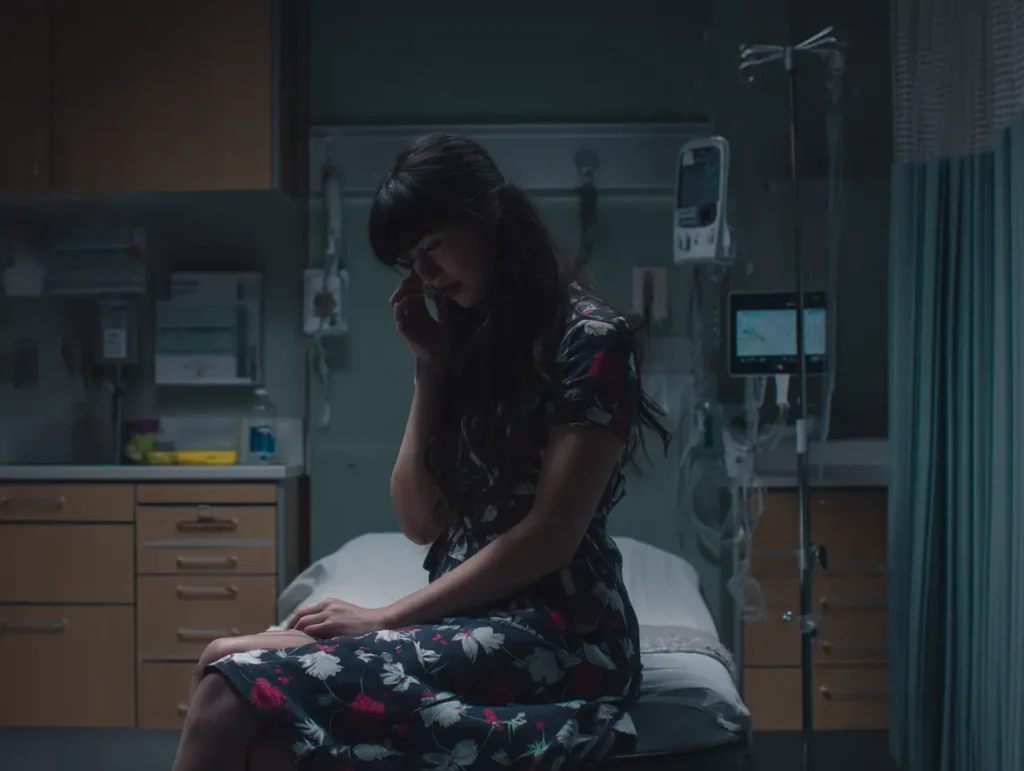

She arrived forty minutes later, coat buttoned wrong, hair pulled back too tightly, clutching a reusable grocery bag filled with neatly labeled containers. She looked shaken, but composed—like someone determined to prove a point. “I brought everything,” Eleanor said, setting the bag down carefully on the counter. Her voice was brisk, but not sharp.

Tired, if anything. “Chamomile. Lavender. A few others. All washed. All things I’ve used myself for years.” The doctor accepted the bag and glanced inside without judgment. “Thank you,” he said. “This helps.” He motioned toward the small consultation room. Mike and Carrie followed as Eleanor took a seat, her hands folded tightly in her lap.

“I need to ask you directly,” the doctor said gently. “While Maxine was in your care, was she given anything other than food, water, or her prescribed medication?”Eleanor hesitated. Just a beat. “I gave her tea,” she said quietly. “A few sips. I didn’t think it would hurt. It calmed her. She liked being part of it.” Her voice wavered, then steadied. “Nothing else. No supplements. No powders. Nothing like that.”

Carrie swallowed. “Mom… we asked you to stop.” “I know,” Eleanor said, turning toward her daughter. Her eyes were glassy now. “And I should have listened. I truly thought it was harmless. I never would’ve given her anything if I thought—” She stopped, shaking her head. The doctor held up a hand, not to interrupt, but to slow the moment.

“It may be nothing,” he said evenly. “Most garden plants are benign, and many cases like this turn out to have unrelated causes. But given Maxine’s symptoms, we need to be thorough. Testing doesn’t mean blame.” Eleanor nodded, wiping at her eyes. “Of course,” she said. “Whatever you need.”

As she stood to leave, she paused at the doorway, looking smaller than Mike had ever seen her. “I love her,” she said softly. “I would never hurt her.” “I know,” the doctor replied. Mike watched her walk down the hallway, unease settling in his chest—not because Eleanor seemed guilty, but because for the first time, no one in the room sounded certain anymore.

Whatever was hurting his daughter hadn’t been explained away. Only narrowed. The waiting stretched. Not the dramatic kind—no alarms, no shouting—just the slow drag of hours marked by nurses coming and going, IV bags checked, charts updated. Maxine slept, her small body curled in on itself, one hand wrapped loosely around Carrie’s finger.

The results came back in stages. First the plants. The pediatrician returned with a thin folder, his expression careful but calmer than before. “The flowers are benign,” he said. “Chamomile. Lavender. Nothing toxic in isolation. Nothing that would explain this level of reaction.” Carrie let out a breath she hadn’t realized she’d been holding.

“So it wasn’t the tea?” “Not directly,” the doctor said. “At least, not from the plants themselves.” Mike felt the floor shift beneath that word. Not directly. “Then what did it?” he asked. Mike broke first. It wasn’t loud. It wasn’t dramatic.

It was the kind of sound that escaped him before he realized he was making it—a sharp breath, then another, his face folding as he turned away from the bed. He pressed his hands to his eyes, furious at himself, terrified of what had been happening to his daughter while he stood there guessing.

“I don’t understand,” he said hoarsely. “We did everything right. We watched her. We took her in. We—” His voice cracked. “Something is hurting her.” Carrie reached for him, but the doctor was already moving again.

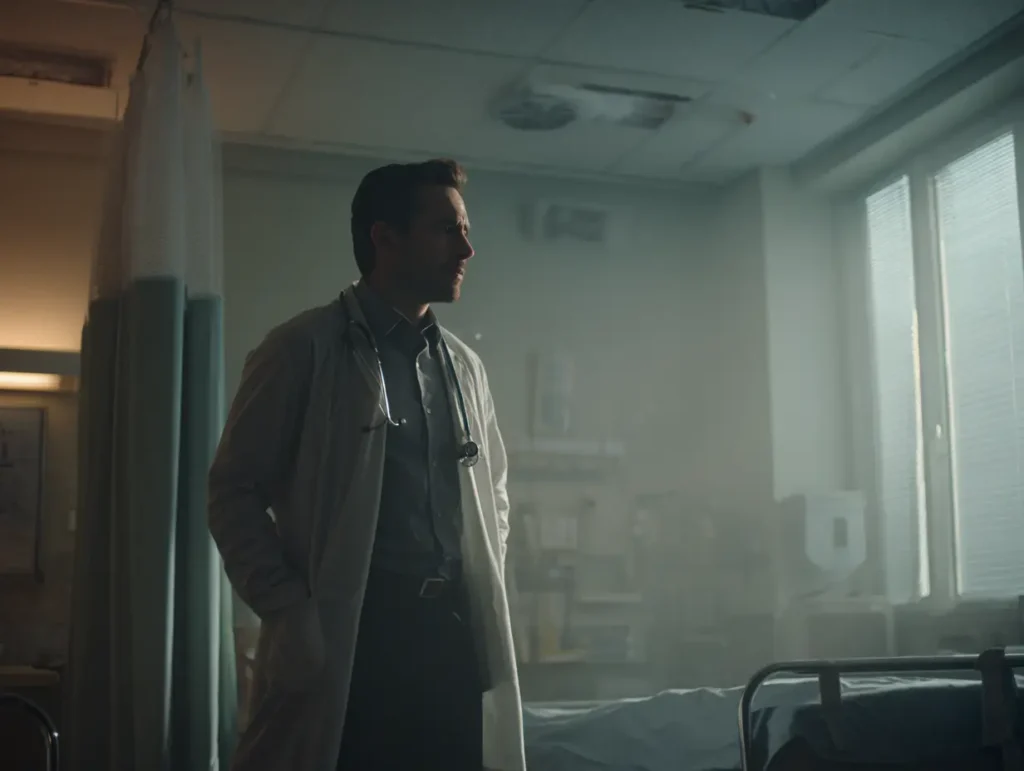

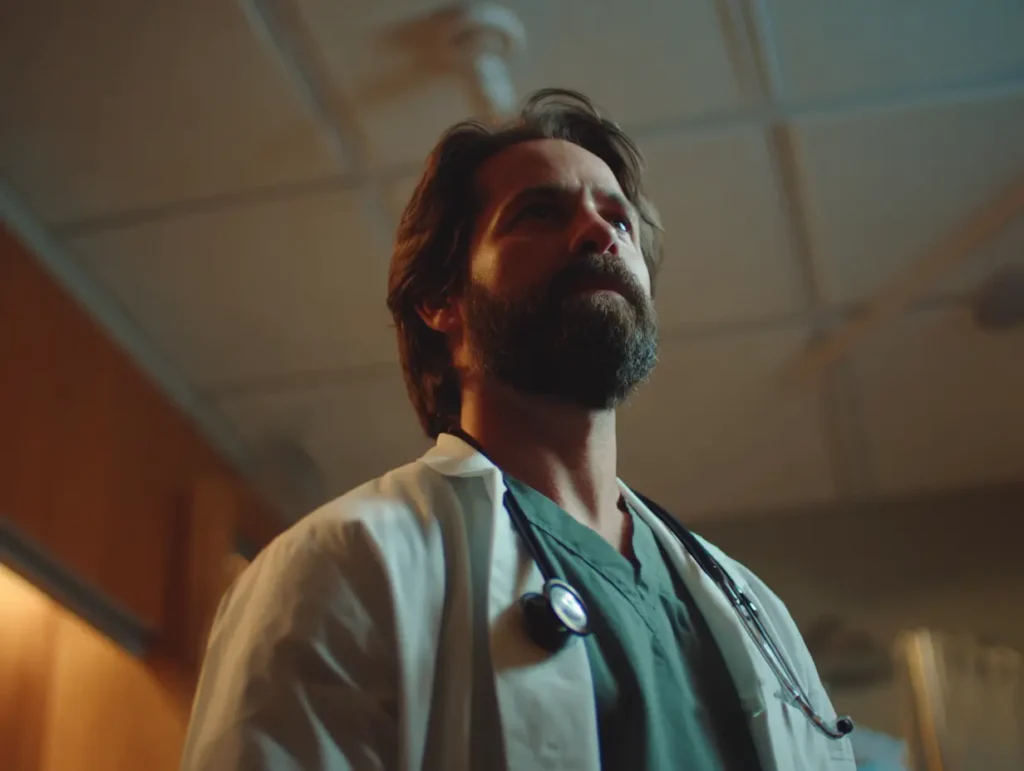

He didn’t speak at first. He stood beside the bed, adjusting the blanket, checking Maxine’s vitals with practiced calm. Then he paused. His fingers hovered, just slightly. He leaned closer, narrowing his eyes—not at her face, not at the monitors, but at her hands.

“Have her nails always looked like this?” he asked quietly. Mike looked up, startled. Maxine’s fingers were small and uneven, the edges of her nails jagged, bitten down to soft, irregular curves. The doctor gently turned her hand under the light.

“She bites them,” Mike said immediately, then hesitated. “She always has. We’ve been trying to stop it.” The words slowed as something clicked into place. “She does it when she’s tired. Or bored.”

The doctor nodded once, his tone changing—not alarmed, but focused. “Has she been outside recently? Playing in soil? A garden?” Mike’s chest tightened. “Eleanor takes her out back every day,” he said. “They dig. She lets her help. Maxine loves it.” For a moment, no one spoke.

“I think,” the doctor said carefully, “we may have found your answer.” He straightened. “We’re going to test what’s under her nails. Immediately.” The waiting came again—but this time it felt sharper, heavier, charged with dread. When the results returned, there was no room left for doubt.

Trace amounts of pesticide. Not enough to harm an adult. But for a child Maxine’s size—repeated exposure, direct ingestion—it explained everything. The fevers. The lethargy. The weight loss. The vomiting. “She wasn’t poisoned intentionally,” the doctor said gently. “But she was exposed. Over time.”

Carrie collapsed into the chair beside Mike, crying—not from guilt, not from anger, but from a relief so sharp it hurt. Eleanor hadn’t meant to harm her. Love, it turned out, wasn’t always enough. “Repeated exposure,” the doctor explained quietly. “Small amounts. Over time. Enough to cause fever, lethargy, appetite suppression. Especially in a child her size.”

Mike sat very still as the words settled. His hands were shaking now, openly, and he didn’t try to stop it. He pressed his palms together, bowed his head, and cried—not loudly, not dramatically, but with the broken restraint of someone who had been holding himself together for far too long.

“She wasn’t harmed intentionally,” the doctor continued. “No one poisoned her. But she was exposed. And her body couldn’t handle it.” Carrie collapsed into the chair beside Maxine’s bed, one hand flying to her mouth. She cried too—quiet, shaking sobs—not from guilt or anger, but from the overwhelming relief of knowing their daughter was going to be okay.

It hadn’t been malice. It had been certainty. Eleanor had trusted what she knew. Too much. Long-held habits, passed down without question. Love, layered with confidence, layered with routine. And none of it had been enough to keep Maxine safe.

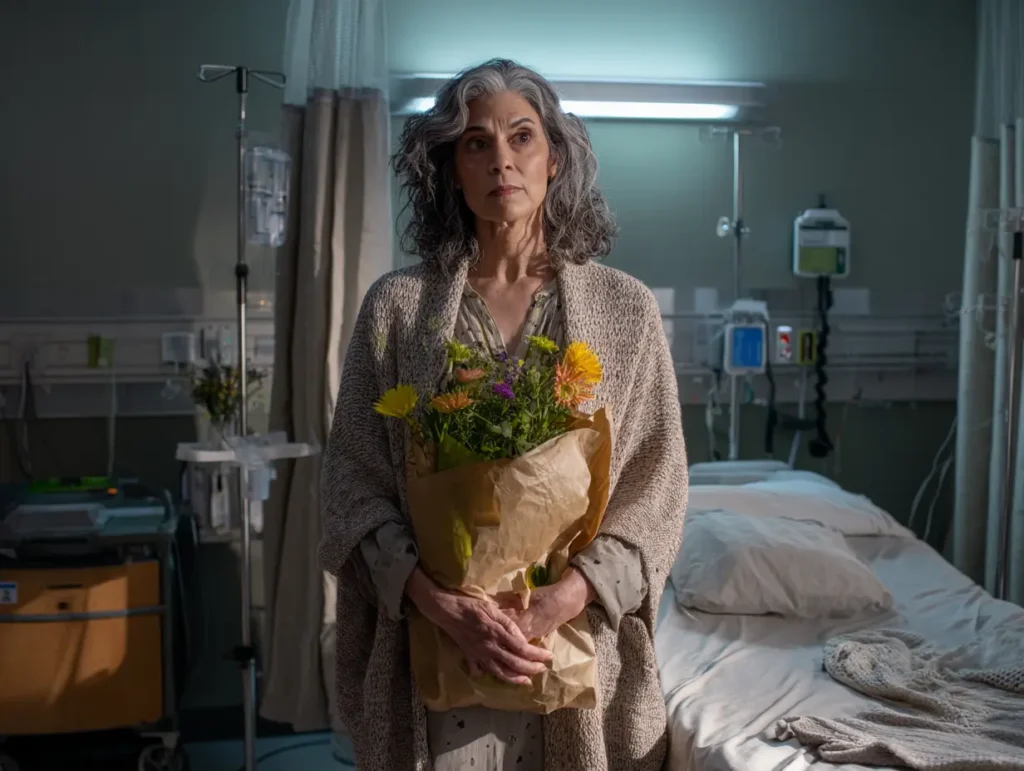

Mike went to Eleanor’s house himself. She was sitting at the kitchen table when he arrived, hands folded, eyes red, waiting. She stood the moment she saw him, words spilling out before he could speak. “I didn’t know,” she said. “I swear to you. I would never—”

“I know,” Mike said, surprising himself with how steady his voice sounded. “That’s why I’m here.” She broke then. Not defensively. Not angrily. Just openly—grief and fear and shame collapsing into one. Mike sat across from her and waited until she could breathe again.

Back at the hospital, Eleanor didn’t rush to Maxine’s bedside. She stopped in the doorway, afraid of doing even that wrong. It was Carrie who took her hand and placed it gently over the blanket. “She needs you,” Carrie said softly.

Maxine’s laughter came back slowly.At first, it was just sound—soft, uncertain, like she was testing whether the world was safe enough to make noise again. Then it grew louder. Sharper. By the time spring settled in, she chased pigeons in the park and demanded snacks with the fierce confidence of a child who felt strong in her body again.

They changed things after that. Shoes stayed on outside. Hands were scrubbed clean before meals. The garden was fenced, the soil turned and replaced. Eleanor followed every rule without question now, watching instead of guiding, asking instead of assuming. Love, this time, came with listening.

Some nights, Mike still woke to check Maxine’s breathing. Some days, Carrie caught herself counting meals, counting hours, counting signs that everything was still all right. But slowly, the fear loosened its grip. They had learned something none of them would forget.

That love doesn’t protect on its own. That certainty can be dangerous.And that paying attention—really paying attention—is sometimes the only thing that keeps a child safe. Maxine grew. And this time, they grew with her.